Abstract

Many studies have observed that African Americans/Black people have comparatively high rates of gonorrhea, chlamydia, and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), often 4-10 times higher than Whites and other racial/ethnic groups.

This research paper delves into the sexual and reproductive health landscape of Black youth in Los Angeles County, employing a community-based participatory research approach grounded in a reproductive justice lens.

The study combines quantitative surveys, in-depth qualitative listening sessions, and culturally sensitive focus groups to comprehensively explore the sexual health experiences, barriers, and preferences of Black youth aged 14 to 30.

The results, based on 281 digital survey responses, 2 virtual listening sessions, and 2 in-person focus groups, highlight the nuanced challenges and opportunities within this demographic.

Key findings encompass:

- disparities in sexual health education,

- barriers to accessing healthcare services,

- communication preferences, and

- the importance of diverse support networks.

The qualitative findings from this study illuminate the multifaceted challenges entrenched within the sexual health landscape for Black youth.

These sessions reveal systemic inadequacies in formal sexual education, underscore cultural hesitancy’s persistence, and emphasize the prevailing healthcare disparities disproportionately impacting this demographic.

Keywords: Black youth, comprehensive sex education, reproductive health, Sexually transmitted infections

Download the Full Report – Sexy & Smart: Extracting Truths about Sex Education for Black Youth »

From 2015 to 2019, HIV diagnosis rates consistently underscored a heightened prevalence among non-Hispanic Black individuals compared to their counterparts in other racial and Hispanic-origin groups (CDC, 2021).

An important stride in addressing sexual health concerns in California is reflected in legislation mandating public and charter schools to deliver comprehensive sexual health education, at least once in high school and once in middle school, through the California Healthy Youth Act (CHYA).

The scope of comprehensive sexual health education, as dictated by state law, encompasses instruction on human development and sexuality, including pivotal topics such as pregnancy, contraception, and sexually transmitted infections (California Department of Education, 2023).

However, despite these legislative initiatives, pronounced disparities persist in the realm of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) for Black youth, particularly among Black girls, in instances of syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia (Division of HIV and STD Programs (DHSP), 2022).

Recent years have borne witness to a growing recognition of the imperative for tailored sexual health education and support services exclusively curated for Black youth (Zellner Lawrence et al., 2016; Dorsey et al., 2022).

Acknowledging the exigency to comprehend their unique experiences, challenges, and perspectives, this research endeavors to undertake a comprehensive exploration and analysis of the sexual health needs of Black youth.

This endeavor embraces a multifaceted approach, inclusive of a comprehensive survey, listening sessions, and focus groups, all within the guiding principles of reproductive justice. Situated within a foundational framework of reproductive justice, the study is attuned to the intersectionality of race, gender, and socioeconomic factors.

Aiming to employ a reproductive justice lens, the research aspires to amass comprehensive data on cultural norms, communication channels, and lived experiences associated with the sexual and reproductive health of Black youth.

In amplifying the voices of Black youth, the research endeavors to contribute substantially to the creation of culturally relevant programs and resources designed to foster positive sexual health outcomes.

With a dual focus, the research seeks, firstly, to investigate the reproductive health status and requirements of Black youth and young adults within the expansive geography of Los Angeles County.

Secondly, it aims to elucidate the intricate web of sexual health communication channels and available health options.

The research thus commits to a critical assessment of the quality and efficacy of the sexual health information and dialogues accessible to this demographic.

Literature Review

Sexual Health Disparities among Black Youth

Numerous studies have highlighted the existence of sexual health disparities among Black youth, including higher rates of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), unintended pregnancies, and limited access to healthcare services (Evans et al., 2020, Dorsey et al., 2022).

These disparities can be attributed to various factors, such as socio-economic inequities, systemic barriers, and cultural stigma (Salam et al., 2016).

Understanding these disparities is crucial for the development of targeted interventions that address the specific challenges faced by Black youth. Through a reproductive justice lens, it becomes evident that sexual health disparities among Black youth are not isolated incidents but rather a result of systemic inequities and social determinants of health.

This review will explore the intersectional factors that contribute to these disparities, including racial discrimination, limited access to healthcare, economic disparities, and lack of comprehensive sex education. Understanding these structural challenges is crucial for developing interventions that address the unique needs and realities of Black youth.

Ultimately, because these sexual health disparities are not the fault of Black youth rather the result of a system that fails to meet the needs of youth (Boutrin & Williams, 2021).

Importance of Youth Inclusive Approaches

Research suggests that traditional sexual health education approaches may not effectively engage and meet the needs of Black youth (Mon Kyaw Soe et al., 2018, Dorsey et al., 2022); mainly due to the lack of a holistic approach, and medical inaccuracies (Schalet et al., 2014).

Youth-inclusive approaches, rooted in their unique cultural contexts and experiences, have been shown to be more effective in promoting positive sexual health outcomes.

By involving Black youth in the development of sexual health programs, interventions can be tailored to their specific needs, fostering a sense of ownership and empowerment (Salam et al., 2016).

Bridging Gaps through Culturally Relevant Programs

Culturally relevant sexual health programs that consider the unique socio-cultural contexts and challenges faced by Black youth are essential for achieving equitable and inclusive sexual health outcomes (Vanwesenbeeck, 2020, Dorsey et al., 2022).

By reviewing existing literature on culturally relevant interventions, this research paper aims to identify successful strategies that have addressed sexual health disparities among Black youth and provide recommendations for the development and implementation of future programs.

Adopting a reproductive justice lens ensures that these strategies account for the broader context of systemic inequities and empower Black youth in their sexual health journey.

Methodology

This research paper utilizes a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to ensure the active involvement of Black youth and community stakeholders in all stages of the research process.

CBPR recognizes the importance of collaboration, shared decision-making, and community empowerment. The methodology is designed to center the voices and experiences of Black youth (ages 14-30) while adhering to ethical guidelines and maintaining confidentiality.

In addition to a comprehensive survey, this research paper acknowledges the importance of listening sessions and focus groups as valuable tools in capturing the experiences and perspectives of Black youth.

By facilitating open and inclusive dialogues, these sessions provide a platform for Black youth to share their thoughts, concerns, and aspirations related to sexual health.

The insights gathered from listening sessions and focus groups will complement the survey data and provide a more nuanced understanding of their needs and preferences.

Data Collection Methods

Comprehensive Survey (N = 281):

A survey questionnaire developed based on research objectives and guided by reproductive justice principles. The survey was designed to gather quantitative data on sexual health knowledge, behaviors, access to healthcare, and experiences of discrimination.

It was administered online and in person, utilizing culturally sensitive and inclusive language. People were eligible for the study if they were ages 14–30, spoke English, self-identified as Black, African American, or of African-descent, and currently resided in Los Angeles County.

Survey respondents received a $10 Starbucks gift card as an incentive to complete the survey.

Listening Sessions (N = 26):

Interactive listening sessions were organized to create a safe and supportive space for Black youth to share their perspectives, concerns, and aspirations regarding sexual and reproductive health.

Trained facilitators used open-ended prompts to encourage dialogue and promote in-depth discussions. The sessions were audio recorded (with participant consent) to capture the richness of the conversations. People who interacted with the survey were invited to participate in the virtual listening sessions.

Listening session participants received a $15 Target gift card after participating in a virtual listening session via zoom on either August 17th or August 23rd, 2023.

The virtual listening session participants were invited from the pool of survey respondents. During these virtual listening sessions participants were asked to openly discuss their experiences, challenges, and needs related to sexual health.

By amplifying voices that are often underrepresented, these sessions yield valuable qualitative insights, informing the development of culturally sensitive policies, programs, and interventions.

Furthermore, they serve to reduce stigma, empower participants, foster trust, and enhance cultural competency among facilitators and organizations.

Ultimately, the goal of sexual health listening sessions was to enable more inclusive, equitable, and effective sexual health education and support services, tailored to the unique circumstances and perspectives of the communities they serve.

Although the number of participants was unequal between sessions, all participants participated via the zoom chat feature, and were able to unmute and share audibly.

Focus Groups (N = 13):

Focus groups were conducted with diverse groups of Black youth to explore specific themes and topics related to sexual health. These groups provided an opportunity for participants to engage in collective brainstorming, share personal experiences, and offer insights into cultural norms, communication channels, and challenges faced.

Focus group discussions were also audio-recorded (with participant consent) for further analysis. Focus-group participants were recruited in urban and suburban centers via email lists, social media, health clinics, and other places where Black youth and young adults in the community could be reached.

Interested participants were screened via email by staff members, and if they were eligible, a demographic survey was then administered to all eligible participants, who were then self-selected in a focus group hosted at Black Women for Wellness from August 30-31, 2023, based on their availability.

Focus-group participants with rich stories were invited to provide more details on their experiences in in-depth group discussions. Focus group participants received a $40 Target gift card as an incentive.

Results

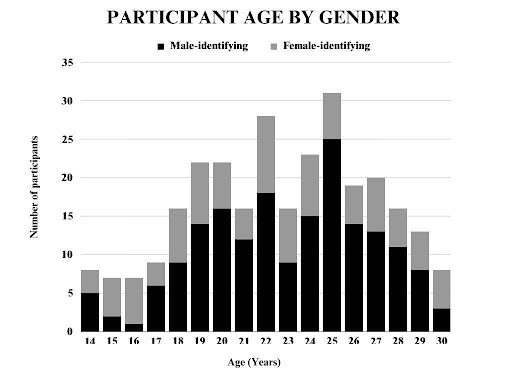

The sexual health survey designed by Black Women for Wellness received a sum of 281 responses from Black youth and young adults in Los Angeles county. In conducting this research, we gathered data on the ages and genders of individuals participating in the study.

Graph 1 depicts the age distribution, which exhibits a fairly diverse range, with participants ranging from 14 to 30 years old, providing a comprehensive snapshot of a varied demographic.

The average age of the participants is approximately 22.03 years, with a median age of 22 years, indicating a relatively balanced distribution. Notably, the most frequently occurring age in the dataset is 25 years.

The standard deviation of 3.57 years suggests a moderate degree of variability in age among the participants. In terms of gender, the dataset includes a total of 100 females and 181 males, highlighting a greater representation of males in the sample.

156 different LA county zip codes were entered by participants, representing geographical diversity within the county. This demographic diversity adds depth to the research, allowing for a nuanced exploration of potential age and gender-related trends or patterns within the dataset.

Further analysis and exploration of this data may uncover valuable insights into the interplay between age, gender, and other potential research variables.

Descriptive Data on Participant Ethnicity:

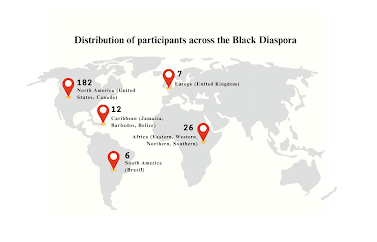

The study includes a diverse cohort of participants representing heritage from various regions within the Black diaspora. Predominantly, Map 1 shows the distribution of survey respondents across geographic locations around the Black diaspora.

The majority of participants identify their families origins within the North American Black diaspora, primarily in the United States with 176 participants, with an additional 6 participants in Canada.

12 survey respondents indicated that their family is from Caribbean nations such as Jamaica, Barbados, and Belize, showcasing a distinct Caribbean influence within the study.

26 participants have connections to different regions in Africa, including Eastern, Western, Northern, and Southern Africa. South America is represented by 2 participants from Brazil, and 4 participants have ties to Europe, particularly the United Kingdom.

Notably, 30 participants identify as 1st generation immigrants, reflecting the study’s inclusion of those who are the first in their immediate families to be born or immigrate to a new country. This comprehensive demographic breakdown underscores the rich diversity within the study’s participant pool, capturing the multifaceted nature of the Black diaspora.

Map 1.

Distribution of Participant Lineage Across the Black Diaspora

Sexual Orientation:

The study’s participant pool exhibits a range of sexual orientations, emphasizing the complexity of individual experiences within the Black diaspora.

The majority of participants identify as heterosexual (straight), comprising 244 (87%) individuals.

While, 13% of respondents identify as LGBTQ+, showcasing the varied ways individuals define and express their identities.

Specifically, 3 participants identify as gay, 6 participants identify as lesbian, and 17 respondents identify as bisexual underlining the importance of recognizing and understanding different sexual orientations within the community.

The study also includes transgender participants, with 9 individuals identifying as such. There are small number of participants (3) who declined to answer, respecting the diversity of comfort levels in sharing personal information.

Socio-economic Status and Educational Background:

The data on participants’ socio-economic status and educational background further enriches the understanding of the Black diaspora’s diverse experiences.

Among the respondents, 59 individuals indicated that they are low-income, signifying financial constraints that impact their ability to meet basic needs and fully participate in society.

Concurrently, 53 participants identify as college students, highlighting the pursuit of higher education within this demographic.

Additionally, 26 participants fall into both the low-income and college student categories, underscoring the intersectionality of socio-economic factors within the community.

Among the participants, there is a notable representation of individuals with a history of foster care. A total of 50 respondents identified as current or former foster youth. Data around the number of foster youth that receive comprehensive sex education is lacking due to barriers such as a lack of provision of comprehensive sexual education by schools serving foster youth and/or foster youth missing the opportunity to attend due to frequent placement changes, which can also lead to low completion rates. (California Department of Social Services, 2023)

Reproductive Health Status:

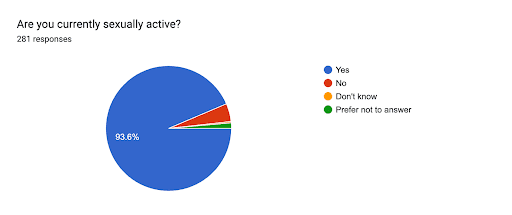

In the survey, participants were asked about their current sexual activity and behaviors, and the responses reflect a range of experiences.

Chart 1 shows that a substantial majority of respondents, constituting 93.6%, indicated that they are currently sexually active.

On the other hand, 4.6% of participants reported not being sexually active at the moment. This diversity in responses, with a significant majority actively engaged in sexual activity, underscores the significance of recognizing and addressing the varied sexual experiences within the Black diaspora.

It also highlights the need for inclusive and comprehensive sexual health education and support initiatives tailored to the diverse needs of the community.

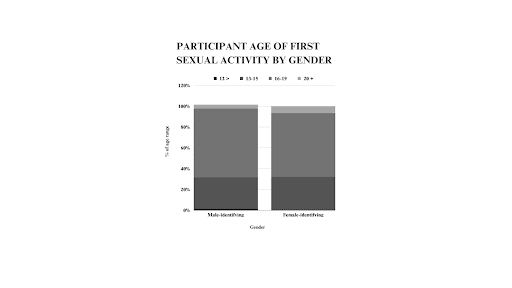

The responses to the question about the age of the first sexual experience provide insight into the diverse experiences of the survey participants. Graph 2 shows that 29% of participants indicated they were between the ages of 13 and 15 years old when they had their first sexual experience.

While a majority of 63% of participants responded, they were between the ages of 16 and19 years old. A smaller percentage of respondents indicated that they were older than 20 years old (6%) and younger than 12 years old (1.6%) at the time of their first sexual experience.

These figures underscore the variation in the age at which individuals within the Black diaspora have their first sexual experiences. The majority of respondents fell within the 16-19 age range, emphasizing the importance of addressing sexual health education and support for this demographic.

In investigating the age at which individuals had their first sexual experience based on gender, a chi-squared test was conducted, yielding a significant result (X-squared = 12.336, df = 4, p-value = 0.01502). This suggests that there are notable differences in the distribution of age categories at first sexual experience among different genders.

Graph 2.

Age of First Sexual Activity, by Gender

In examining participants’ responses regarding their number of sexual partners over the past year, a diverse range of experiences emerged from the analysis. Table 1 displays that a portion of respondents—71 individuals—reported engaging with 2-4 sexual partners during the last 12 months.

Conversely, 120 individuals indicated having a singular sexual partner, while 29 participants reported involvement with 10 or more partners. An additional 34 respondents detailed having 5-9 sexual partners, and 10 individuals disclosed no sexual activity in the preceding year.

The subsequent analysis, as presented in Table 1, elucidated a statistically significant association between participants’ age and the number of sexual partners they had at the .001 level of significance. This underscores the need for targeted sexual health interventions based on the diverse experiences of participants.

| Table 1 Number of Sexual Partners in Last 12 Months, by Age | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

No. Partners |

14-17 | 18-21 | 22-25 | 26-30 | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| 0 | 6 | 19.4 | 3 | 4.7 | 1 | 1.1 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 1 | 13 | 41.9 | 19 | 30.1 | 46 | 48.4 | 42 | 56 | |||

| 2-4 | 6 | 19.4 | 18 | 28.6 | 30 | 31.6 | 17 | 22.7 | |||

| 5-9 | 5 | 16.1 | 16 | 25.4 | 7 | 7.4 | 6 | 8 | |||

| 10≤ | 1 | 3.2 | 7 | 1.6 | 11 | 11.5 | 10 | 13.3 | |||

| Total | 31 | 100 | 63 | 90.4 | 95 | 100 | 75 | 100 | |||

| Note. The Pearson chi-square with Yates correction factor value was 45.7, df = 12, p-value = 0.000007 | |||||||||||

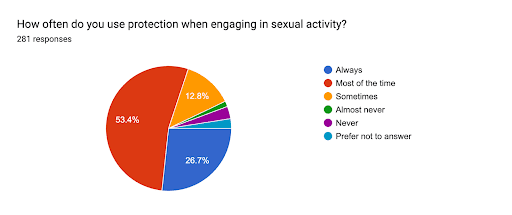

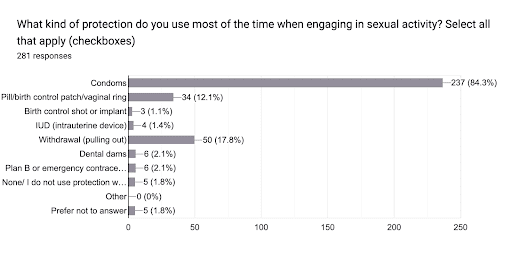

To assess the patterns of protection use during sexual activity, respondents were asked about the type of protection they use most of the time and the frequency of its use.

Graph 3 revealed that condoms were the predominant choice, with 53.4% of participants indicating regular use (most of the time) and 26.7% reporting consistent usage (Always) in Chart 2.

Other methods, such as birth control shots or implants, withdrawal (pulling out), and birth control pills, patches, or vaginal rings, were also reported, but to a lesser extent.

Notably, a subset of respondents mentioned not using any protection at all, with some indicating they almost never or never use protection. This information underscores the importance of understanding and promoting safe sexual practices, emphasizing the diversity of protection methods, and addressing potential gaps in knowledge or access to contraceptives.

Further analysis could explore the relationship between protection use and demographic factors to tailor sexual health education and intervention strategies.

Chart 2

Frequency of contraceptive usage

Graph 3.

Participant Most Used Protection During Sexual Activity

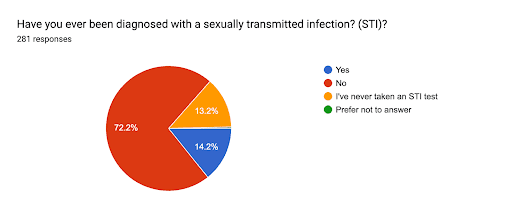

Upon reviewing responses pertaining to the survey question, “Have you ever been diagnosed with a sexually transmitted infection (STI)?,” chart 3 shows that 13.2% of participants have not undergone an STI test.

Within the cohort that did undergo testing, 14.2% divulged positive STI diagnoses, while 72.2% received negative results. The proportion of individuals abstaining from STI testing and individuals that have received positive STI results implies potential gaps in sexual health awareness or accessibility to testing services.

Moreover, the prevalence of positive STI diagnoses accentuates the exigency for heightened education on safe sexual practices and regular testing. The diverse array of responses underscores the intricate terrain of STI awareness and testing behaviors among the surveyed demographic, thereby illuminating avenues for targeted interventions to fortify sexual health.

This research sheds light on critical facets of sexual health perceptions, underscoring the imperative for multifaceted strategies to enhance awareness, access, and education within this domain.

Chart 3.

Previous Sexually Transmitted Infections (STI) diagnoses

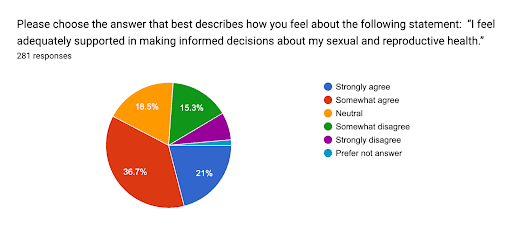

Survey participants answered a series of likert scale questions to measure attitudes, opinions, or perceptions around sexual health. The analysis of respondents’ feelings about the statement “I feel adequately supported in making informed decisions about my sexual and reproductive health” reveals a diverse range of sentiments.

Chart 4 shows that a majority of respondents express a high level of agreement, with 21% strongly agreeing and 36.7% somewhat agreeing. On the other hand, 15.3% of participants somewhat disagree and 7.1% strongly disagree with the statement, indicating a portion of the surveyed individuals feel inadequately supported.

The remaining respondents either chose a neutral stance (6.1%) or preferred not to answer (1.9%). Table 2 analyzes the relationship between feeling supported in sexual health decision-making by age and gender. In both the female and male groups, the chi-square test results do not provide sufficient evidence to conclude that there is a significant association between gender and feelings of support in sexual health decision-making.

The high p-values suggest that any observed differences are likely due to chance, emphasizing the importance of considering additional analyses or factors in the exploration of these associations.

Chart 4.

Participant Attitude on Sexual Reproductive Health Support

Table 2.

Participant Feeling of Support in Sexual Health Decision-Making, by Gender and Age

| Gender | Age | Neutral | Somewhat agree | Somewhat disagree | Strongly agree | Strongly disagree |

| Female | 14 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 15 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 16 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| 17 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 18 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 19 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| 20 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| 21 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | -0 | |

| 22 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 3 | |

| 23 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| 24 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 25 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| 26 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 27 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 28 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 29 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| Total | 22 | 36 | 18 | 14 | 8 | |

| Male | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 15 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 16 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 17 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| 18 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |

| 19 | 1 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 20 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | |

| 21 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | |

| 22 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 4 | |

| 23 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | |

| 24 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 0 | |

| 25 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 4 | 0 | |

| 26 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| 27 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | |

| 28 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 0 | |

| 29 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| 30 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 30 | 67 | 25 | 45 | 12 | |

| Total | 52 | 103 | 43 | 59 | 20 |

Note. The Pearson chi-square with Yates correction factor value was 25.1, df = 75, p-value = 0.99 for the female group

The Pearson chi-square with Yates correction factor value was 0.3, df = 75, p-value = 1 for the male group

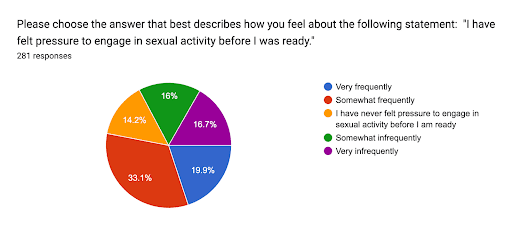

Upon analyzing the responses to the statement “I have felt pressure to engage in sexual activity before I was ready,” chart 4 reveals distinct patterns in participants’ experiences. A significant portion, comprising 19.9%, reported feeling pressured “very frequently,” while a slightly larger proportion, 33.1%, indicated experiencing pressure “somewhat frequently.”

On the contrary, a noteworthy percentage of respondents, 14.2%, stated that they have never felt pressure to engage in sexual activity before they were ready. Additionally, 16% mentioned feeling pressured “somewhat infrequently,” and 16.7% reported experiencing pressure “very infrequently.”

These findings emphasize the variability in individuals’ encounters with pressure related to sexual activity and underscore the importance of promoting open discussions and support systems to address such experiences.

Chart 4.

Participant Attitude on Sexual Pressure

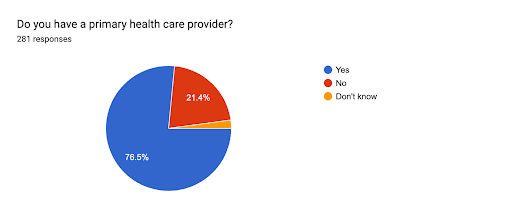

Access to Health Care Services:

Chart 5 shows that 76.5% of participants indicated having access to a primary health care provider. Conversely, 21% of respondents explicitly stated they do not have a primary health care provider, while a marginal 2.1% admitted uncertainty regarding having a primary care provider.

This distribution of responses underscores the prevalence of access to primary health care services within the surveyed demographic. The substantial percentage of individuals with an identified primary health care provider suggests a positive trend in healthcare engagement, fostering a potential avenue for targeted health interventions and awareness campaigns.

Meanwhile, the proportion of participants expressing uncertainty emphasizes the importance of initiatives aimed at enhancing awareness and facilitating access to primary health care services.

Chart 5.

Participant Access to Primary Health Care

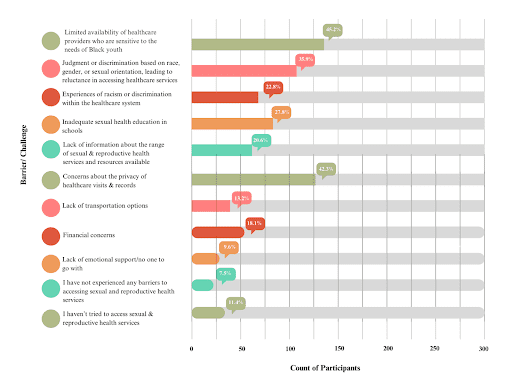

However, contradictions were found as we explored the various barriers and challenges faced by individuals in accessing sexual and reproductive health services. This revealed a nuanced narrative surrounding the challenges faced by individuals, particularly Black youth, in accessing sexual and reproductive health services.

The data highlights significant barriers, as a significant 45.2% of respondents identified the limited availability of healthcare providers sensitive to the needs of Black youth as a major barrier. Judgment or discrimination based on race, gender, or sexual orientation, leading to reluctance in accessing healthcare services, was reported by 101 respondents, or 35.8% of the participants.

Moreover, experiences of racism or discrimination within the healthcare system were voiced by 64 individuals, or 22.7% of the surveyed population. Concerns about sexual health education in schools were expressed by 78 respondents, or 27.7% of the total.

A lack of information about available sexual and reproductive health services and resources was noted by 58 participants, representing 20.6% of the respondents. Privacy concerns during healthcare visits and records emerged as a significant issue for 119 respondents, making up 42.2% of the surveyed population, highlighting the importance of confidentiality in healthcare settings.

Furthermore, potential education on healthcare services and resources is required by law to be confidential. Transportation challenges, financial concerns, and a lack of emotional support were reported by varying percentages of participants, with 37 (13.1%), 51 (18.1%), and 27 (9.6%) respondents, respectively.

Data from Graph 5 emphasizes the diverse obstacles individuals face in seeking sexual and reproductive health services. Notably, a subset of respondents (32) revealed they hadn’t attempted to access such services, making up 11.3% of the surveyed population, indicating a potential gap in outreach or awareness.

Conversely, 21 respondents reported not experiencing any barriers, constituting 7.4% of the participants, suggesting that, for some, the current system adequately meets their needs. Collectively, these findings underscore the complexity of barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services, emphasizing the need for tailored interventions that address the diverse concerns identified by the surveyed population.

Table 3 presents the distribution of participant responses regarding barriers to accessing sexual health services, categorized by gender. Each row corresponds to a specific barrier or challenge, and the counts represent the total number of times that choice was selected across all participants.

Participants were asked to select all applicable barriers from a checklist, resulting in a comprehensive view of their experiences. The chi-square test (χ² = 17.876, df = 10, p-value = 0.057) was employed to assess the association between gender and reported barriers.

The p-value of 0.057 is slightly above the conventional significance level of 0.05. While it doesn’t reach the traditional threshold for statistical significance, it is close, suggesting a marginal association. Further investigation, possibly through a larger sample size or a more targeted study design, might provide more conclusive evidence regarding the association between gender and barriers to accessing sexual health services.

Graph 5.

Barriers to Accessing Healthcare Services

| Table 3.

Distribution of Participant Responses – Barriers to Accessing Sexual Health Services, by Gender |

|||

| Barrier/Challenge | Female | Male | Grand Total |

| Concerns about the privacy of healthcare visits and records | 41 | 68 | 109 |

| Experiences of racism or discrimination within the healthcare system | 18 | 35 | 53 |

| Financial concerns | 14 | 28 | 42 |

| I have not experienced any barriers to accessing sexual and reproductive health services | 12 | 6 | 18 |

| I haven’t tried to access sexual & reproductive health services | 15 | 19 | 34 |

| Inadequate sexual health education in schools | 19 | 45 | 64 |

| Judgment or discrimination based on race, gender, or sexual orientation, leading to reluctance in accessing healthcare services | 36 | 456 | 92 |

| Lack of emotional support/no one to go with | 9 | 18 | 27 |

| Lack of information about the range of sexual and reproductive health services and resources available | 15 | 39 | 54 |

| Lack of transportation options, | 6 | 26 | 32 |

| Limited availability of healthcare providers who are sensitive to the needs of Black youth | 39 | 92 | 131 |

| Total | |||

| Note. The Pearson chi-square with Yates correction factor value was 17.876, df = 10, p-value = .057. | |||

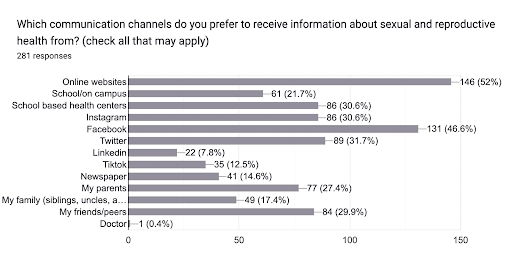

The analysis of responses regarding preferred communication channels for sexual and reproductive health information reveals a diverse landscape of preferences among the surveyed individuals. In graph 6 the predominant choice selected by 52% of respondents is online websites, reflecting a reliance on digital platforms for information.

Social media channels emerged as the next significant source, with 46.6% of participants expressed using facebook, 30.6% participants identified instagram, and 31.7% for twitter as a preferred source for sexual health communications, highlighting the pivotal roles social media plays in disseminating sexual health information.

Despite the prevalence of digital channels, traditional mediums such as newspapers (14.3%) and direct engagement with parents (27.4%) maintain a noteworthy presence. School-based health centers emerge as a major channel, with 30.6% of participants expressing a preference for this on-site resource.

The influence of interpersonal connections is evident, as 29.9% favor information from friends and peers, while 17.4% seek guidance from family members such as siblings, uncles, and aunts. These findings emphasize the importance of employing a comprehensive, multi-channel approach to effectively address the diverse communication preferences of the target audience in sexual and reproductive health outreach efforts. (*insert comms/age graph*)

Graph 6.

Participant Preferred Sexual Reproductive Health Communication Channels

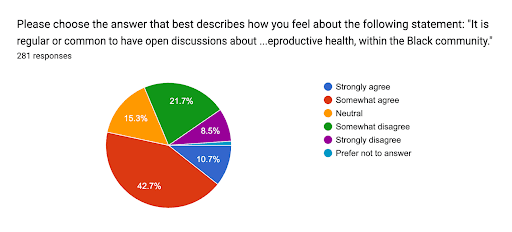

The survey respondents were asked to express their views on the regularity of open discussions about health issues, including mental health and reproductive health, within the Black community. Chart 5. revealed a diverse range of opinions, with 53.4% of participants either strongly or somewhat agreeing that such discussions are common.

This suggests a prevailing sentiment among a majority of respondents that open conversations about health-related matters occur regularly within the Black community. On the contrary, 30.2% of participants expressed some level of disagreement, indicating a notable portion with differing perspectives on the frequency of these discussions.

A small fraction (1.1%) chose not to disclose their opinion. These findings shed light on the varied perceptions within the surveyed population regarding the prevalence of open dialogues surrounding health topics in the Black community, emphasizing the need for nuanced approaches to addressing health communication within this demographic.

Chart 5.

Participant Rating of Perceived Openness of Sexual, Mental Health Dialogue in the Black Community

Health Education Options:

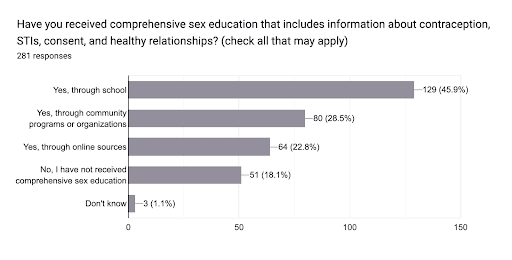

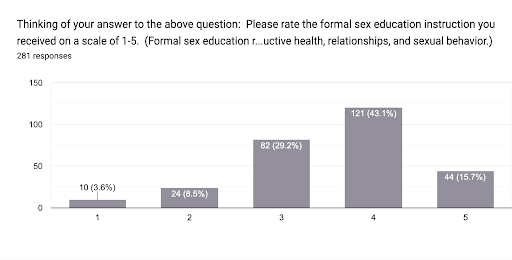

`The empirical analysis of survey responses provides noteworthy insights into the landscape of comprehensive sex education, revealing a commendable 80.8% prevalence among respondents that have received comprehensive sex education in Graph 6.

This indicates a widespread exposure to structured programs encompassing pivotal facets such as contraception, STIs, consent, and healthy relationships. A score of 1 is a rating of poor, meaning that the participant felt they didn’t learn anything, and a score of 5 is a rating of excellent, meaning that participants felt empowered to make informed decisions about their sexual health.

Despite the substantial coverage, the research underscores a nuanced perspective by incorporating the average rating of sex education, which stands at a moderate 3.59 on the 1-5 scale. Graph 7 shows the frequency of each rating.

This suggests a potential variance in the quality and efficacy of the educational initiatives, highlighting the need for targeted improvements. The findings imply that while a majority has encountered comprehensive sex education, the perceived effectiveness varies, necessitating a strategic approach for refinement.

Table 4 compares participants’ rating of the comprehensive sex education they received to the combination of CSE locations. The chi-square test (χ² = 77.99, df = 28, p-value = 0.0) revealed a significant association between participant ratings and the location of CSE.

Notably, the combination of School/ Online sources garnered the highest participant satisfaction, with approximately 77.8% rating it the highest (5). In contrast, participants who exclusively received CSE from online sources yielded only 11.1% with the highest rating.

The School/ Community-based programs combination demonstrated a robust 59.1% satisfaction rate with the highest rating. Interestingly, community-based programs alone received a higher satisfaction rate (6.4%) compared to school-based programs alone (6.8%).

In terms of participant volume, the majority (94) received CSE exclusively from school-based programs, signaling the continued significance of traditional educational settings. These findings underscore the importance of a thoughtful integration of traditional and online resources in designing CSE programs.

Graph 6.

Percentage of Participants Who Received Formal Sex Education, by Location.

Graph 7.

Participant Rating of Received Formal Sex Education

| Table 4.

Participant Rating of Comprehensive Sex Education (CSE) Received |

|||||||||||

| Rating (1 – 5) | |||||||||||

| 1 ________ |

2

________ |

3

________ |

4

________ |

5

________ |

|||||||

| CSE Location | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | Total |

| Community-based programs | 1 | 0.44 | 2 | 0.87 | 17 | 7.4 | 15 | 6.6 | 13 | 4.6 | 48 |

| Community-based programs / Online sources | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 1.1 | 6 |

| Online sources only | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 20 | 8.7 | 20 | 8.7 |

5 |

1.8 | 45 |

| School only | 1 | 0.44 | 4 | 1.7 | 19 | 8.3 | 58 | 2 | 12 | 4.3 | 94 |

| School/ Community-based programs | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 7 | 3.1 | 13 | 4.6 | 6 | 2.1 | 22 |

| School/ Community-based programs/online sources | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 0.7 | 2 | 0.7 | 4 |

| School/ Online sources | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 8.7 | 7 | 2.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 9 |

| Total | 7 | 18 | 15 | 7 | 3 | 229 | |||||

| The Pearson chi-square with Yates correction factor value was 77.99, df = 28, p-value = 0.0 | |||||||||||

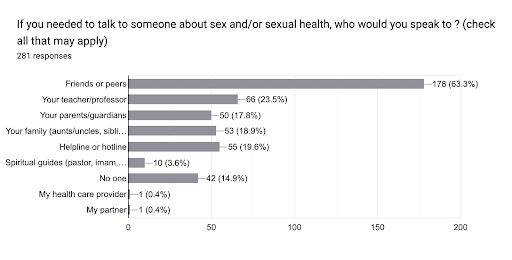

Graph 8. illustrates individuals’ preferred confidants for discussing sex and sexual health, and reveals intriguing patterns. A majority of respondents, comprising 63.3%, expressed a preference for turning to friends or peers, highlighting the significance of peer support in these discussions.

Notably, 23.5% indicated a level of comfort in approaching their teacher or professor, underlining the role of educational figures in providing guidance on sexual health matters. 18.9% of participants stated they would trust family members like aunts, uncles, and siblings to have these kinds of conversations.

Helplines or hotlines were considered a valuable resource by 19.6% of respondents, emphasizing the importance of accessible and confidential support channels. A smaller percentage, 14.9%, reported that they would not discuss sex or sexual health with anyone, underscoring the existence of barriers to open communication.

Furthermore, 3.6% of participants named spiritual mentors like pastors or imams, among the diverse array of individuals that people can consult for guidance. The data highlights the need for fostering a supportive environment across various spheres to encourage open conversations about sex and sexual health.

Graph 8.

Participant In-person Sexual Health Communication Preferences

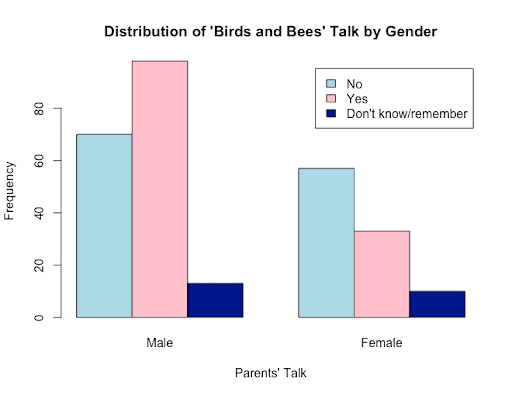

Graph 9 depicts the distribution of responses to the “Birds and Bees” talk based on gender and the frequency of responses for each category. Upon examination of parental communication patterns on the topic of sexual readiness, consent, and birth control, stratified by gender.

The data, presented as sums across male and female respondents, revealed distinct patterns in responses. A noteworthy finding emerged in the category of “No,” where 70 males and 57 females indicated a lack of engagement in the ‘birds and the bees’ conversation.

Conversely, in the “Yes” category, 98 males and 33 females reported having had such discussions. The “Don’t know/remember” category exhibited a moderate response, with 13 males and 10 females expressing uncertainty or forgetfulness regarding the occurrence of these conversations.

Testing for statistical significance leveraging Pearson’s Chi-squared test, the calculated test statistic of 11.588 with 2 degrees of freedom yielded a p-value of 0.003046. The resulting p-value, below the conventional significance threshold of 0.05, signifies a statistically significant relationship between the variables.

Consequently, the null hypothesis, positing no association, was confidently rejected. This compelling evidence supports the contention that gender plays a discernible role in the likelihood of individuals having received comprehensive discussions about sexual readiness, consent, and birth control from their parents or guardians.

These findings contribute valuable insights into the dynamics of familial communication on intimate topics, shedding light on the potential influence of gender in shaping these crucial conversations.

Graph 9.

Sexual Health Parental Communication by Gender

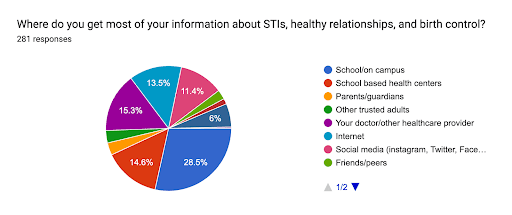

Graph 10. shows the sources from which individuals acquire information about STIs, healthy relationships, and birth control, and reveals diverse patterns of information-seeking behavior.

Notably, the majority of respondents appear to rely on formal channels, with school-based health centers being a prominent source, constituting 25.98% of the responses, followed closely by information obtained from trusted adults, including parents/guardians, representing 23.13% of responses.

It is interesting to observe the significant influence of digital platforms, such as social media and the internet, constituting 22.78% and 19.21% of responses, respectively, indicating a shift towards online resources for sexual health education.

Moreover, a subset of respondents reported seeking information from personal research (6.76%), emphasizing the importance of self-driven knowledge acquisition. The presence of individuals who claim to receive information from ‘Nowhere’ (2.14%) highlights a potential gap in sexual health education accessibility or a subgroup that may not actively seek such information.

Graph 10.

Source of Sexual Health Information (STIs, Healthy Relationships, and Birth Control)

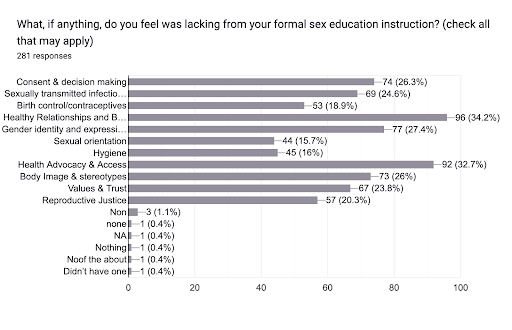

Graph 11 sheds light on the multifaceted perspectives regarding the adequacy of formal sex education, with a notable portion expressing satisfaction (6.8%) and others identifying specific areas of improvement. The distribution of concerns encompasses a spectrum of topics, revealing varying emphasis among respondents.

Noteworthy categories include Healthy Relationships and Boundary Setting (34.2%), Gender Identity and Expression (27.4%), Body Image & Stereotypes (26%), and Consent & Decision Making (26.3%). Additionally, considerations for Sexual Orientation (15.7%), Health Advocacy & Access (16%), Values & Trust (23.8%), and Reproductive Justice (20.3%) highlight the diverse needs and expectations within sex education.

These findings underscore the importance of tailoring educational programs to address the complexity of human sexuality comprehensively, emphasizing inclusivity and responsiveness to the diverse perspectives and needs of learners.

Graph 11.

Comprehensive Sex Education Topics that are Missing or Need Improvement

Graph 11.

Sex Ed Topics participants felt needed to be added or improved in sex ed curriculum

Qualitative Data

Results from the listening sessions revealed several key insights regarding sex education experiences and sexual health in the context of the participants’ lives. Facilitators asked a total of 12 discussion questions intended to elicit feedback around reproductive health and sex education experiences.

Regarding their encounters with sex education, participants mentioned the absence of formal sex education classes in their schools and challenges related to misinformation. Some participants expressed dissatisfaction with the depth of information provided in school-based sex education.

When discussing conversations with parents about sex, there was a mixed response, with some feeling uncomfortable and others open to dialogue but highlighting the need for better education.

The participants recognized the importance of sexual health discussions within the Black community, emphasizing the need for comprehensive programs for both men and women.

They also identified specific topics, such as reproductive options beyond pregnancy, consent education, and the long-term consequences of sexual decisions, as crucial for young Black individuals.

Furthermore, participants shared instances where societal norms influenced their perceptions of sexual health and decisions, often referencing media portrayal and societal pressures. They also recounted experiences of feeling unheard or dismissed in healthcare settings, and some mentioned micro-aggressions encountered in healthcare and educational contexts.

Overall, these insights underscore the significance of culturally competent and comprehensive sexual health education, open communication between youth and healthcare providers, and addressing societal norms in the context of sexual health discussions.

The focus group participants were invited to the Black Women for Wellness office in Leimert Park. Participants were asked to engage in sexual health discussions with the goal of identifying lived and observed challenges that Black youth face in terms of reproductive health, access to health services, and health education.

Participants were also asked to review a portion of Black Women for Wellness’s Get Smart B4U Get Sexy curriculum and find solutions to enhance the curriculum to better address the challenges Black youth may encounter when obtaining sexual reproductive health services, information, and resources.

During these focus groups participants were presented with a summary of the findings from our sexual survey. The key topics that emerged during the focus groups revealed the following key themes:

- Culturally Competent Health Education Programs: Participants agreed on the necessity to develop culturally relevant and sensitive sex education programs tailored specifically for Black youth. These programs should address the unique cultural norms and values of the community while providing comprehensive and accurate information on sexual health. Participants discussed open dialogue about key topics like consent, and sexual readiness including emotional well-being check-ins.

- Collaboration with Schools: Participants recommended community-based organizations to partner with schools to integrate comprehensive and culturally competent sexual health education into the curriculum, ensuring that students receive accurate information from a young age. Participants noted legislation agreeing in Florida preventing teachers from saying, “Gay”, they did not want to implicate or burden teachers to discuss sexual health but schools and school boards should be intentional in assuring all youth receive equitable sexual health education.

- Online Resources and Apps: Participants recommended creating user-friendly online platforms and apps that offer information on sexual health, including contraception, STIs, and healthy relationships. Emphasis was placed on ensuring that these resources are accessible and engaging for Black youth.

- Youth Advisory Boards: Participants recommended the formation of youth advisory boards that actively participate in shaping sexual health programs, policies, and resources to ensure they are relevant and effective for Black youth.

- School Board Advocacy Program: Consistent with recommendation to partner with schools; participants agreed on establishing an advocacy program aimed at providing recommendations to school boards on improving sexual health education. This program could involve collaborating with local community organizations, parents, and students to create a task force that regularly reviews and assesses the effectiveness of existing sexual health education curricula. The task force can then compile recommendations based on community needs, cultural sensitivity, and the latest research in sexual health education. These recommendations can be presented directly to school board members, offering actionable insights for enhancing the quality and inclusivity of sexual health education in schools. This approach ensures that community voices are heard and that sexual health education is responsive to the needs of Black youth.

Discussion

Community Engagement in Health Discussions:

A substantial portion of respondents (43%) strongly agreed and (11%) agreed it is regular or common to have open discussions about health issues, including mental health and reproductive health, within the Black community.

54% of respondents expressed a positive stance on the regularity of open discussions suggests a growing recognition and acceptance of the importance of discussing various health aspects, including mental health and reproductive health, within the community.

However, it’s worth noting that 22% of respondents somewhat disagree and (8.5%) strongly disagreed, indicating that there are still individuals who perceive a lack of openness in health discussions.

Furthermore, graph 7 illustrates that the majority of youth in the sample prefer discussing sex and sexual health with their peers or friends. Moreover, data shows that peer to peer educational programming is recognized as a key component of effective STI prevention strategies (Mon Kyaw Soe et al., 2018).

We recommend further research and funding to assist in the development of The California Healthy Youth Act (2016) and SB 89 compliant peer to peer sex education programs.

The two California bills ensure reproductive and sexual health care for youth, including youth in care and non-minor dependents. More study on this topic would allow for the effective incorporation of peer to peer support and educational programs.

We recommend more engagement surrounding encouraging and facilitating open dialogue around sexual reproductive health and accurate sex education needs to happen at community levels.

A significant subset of respondents (42.7%) conveyed optimism about the frequency of open health discussions within the Black community, reflecting an evolving acknowledgment of the importance of addressing diverse health issues, including mental and reproductive health.

However, 8.5% staunchly disagreed, underscoring persistent perceptions of a dearth in open health dialogues. Notably, a preference for discussing sex with peers emerged (63.3%), emphasizing the need for heightened community-level efforts in fostering open conversations and endorsing comprehensive sexual education.

Varied Satisfaction with Sexual and Reproductive Health Services:

Analysis of satisfaction with sexual and reproductive health services unveiled a mixed sentiment among Black youth. While 32.4% and 21% expressed agreement and strong agreement, respectively, with service quality, a significant 24.2% held dissenting views.

This dichotomy calls for targeted improvements, and investigation into the quality and inclusivity of comprehensive sex education across California counties emerges as a pertinent avenue for further exploration.

Communication Preferences for Sexual Health:

A majority (63.3%) preferred discussing sexual health with friends, emphasizing the pivotal role of peer relationships. Teachers (23.5%) and parents (17.8%) were also significant channels, reflecting the importance of formal and familial avenues.

Noteworthy is the reliance on online platforms, school-based health centers, and friends, prompting considerations for inclusive sex education channels.

Support Networks for Sex and Sexual Health Discussions:

Friends or peers emerged as primary support networks (63.3%), with teachers/professors (23.5%) and parents/guardians (17.8%) closely following.

Insights from focus groups highlighted dissatisfaction with current sex education in schools, warranting a closer examination of potential health education disparities among schools.

Policy Recommendations

Comprehensive Sexual Education: Advocate for comprehensive sexual education programs in schools that are culturally sensitive and inclusive of Black youth experiences. Future research should examine cross country sex education for youth to rate and compare participant satisfaction and effectiveness.

Access to Reproductive Health Services: Increase access to affordable and confidential reproductive health services for Black youth, including STI testing, treatment, and contraception. This could involve expanding school-based health centers, mobile clinics, and telehealth services.

Community-Based Outreach and Education: Invest in community-based organizations that provide culturally competent sexual health education, outreach, and support services tailored to Black youth. These organizations can engage with youth through workshops, peer education programs, and social media campaigns.

Reducing Stigma and Discrimination: Implement anti-stigma campaigns and educational initiatives to combat stigma and discrimination related to STIs, particularly within the Black community. Promote messages of acceptance, support, and destigmatization of STIs.

Addressing Socioeconomic Factors: Address socioeconomic factors that contribute to STI disparities, such as poverty, lack of access to healthcare, and housing instability. Support policies that address economic inequality and provide resources for vulnerable communities.

Culturally Competent Healthcare Providers: Promote diversity and cultural competence training among healthcare providers to ensure that Black youth receive respectful, non-judgmental care. Encourage providers to create welcoming environments where youth feel comfortable seeking sexual health services.

Youth Engagement and Leadership: Involve Black youth in the development and implementation of policies and programs related to sexual health. Create opportunities for youth leadership, advocacy, and peer education to empower them to take ownership of their sexual health.

Data Collection and Research: Improve data collection efforts to better understand STI trends and disparities among Black youth in California. Support research initiatives that explore the underlying factors contributing to these disparities and inform evidence-based interventions.

Addressing Structural Racism: Recognize and address the impact of structural racism on sexual health outcomes for Black youth. Advocate for policies that dismantle systemic barriers and promote equity in access to resources, opportunities, and healthcare services.

Collaboration and Coordination: Foster collaboration among government agencies, community organizations, healthcare providers, educators, and other stakeholders to develop a comprehensive approach to addressing STI disparities among Black youth. Coordinate efforts to maximize impact and ensure that resources are effectively utilized.

Limitations

This research has several limitations that warrant consideration. Firstly, the survey data relied on self-reported responses from participants, introducing the possibility of response bias or inaccuracies due to individual perceptions or interpretations.

Although responses were collected in a semi-anonymous format, with participants not required to disclose their names but providing their email addresses, the potential for social desirability bias or reluctance to share certain information may still exist.

Additionally, in exploring the participants’ sexual health experiences, the survey question pertaining to the first sexual contact was intentionally left open to interpretation, introducing a subjective element that could impact the consistency and reliability of the gathered data.

These limitations should be taken into account when interpreting the findings and generalizing the results to broader populations. Future research endeavors could explore alternative data collection methods or employ validation techniques to enhance the robustness of the study outcomes.

Conclusion

This research stands as a transformative contribution to the sexual health literature concerning Black youth, offering an in-depth exploration of their experiences, challenges, and specific needs. According to the Society of Medicine and Adolescent Health (SAHM), “

Sexuality education should be comprehensive, medically accurate, and culturally competent; promote healthy sexuality; and prepare young people to make healthy sexual decisions.

Instruction in sexuality education should include essential concepts and issues such as sexual orientation, sexual health, gender identity and power dynamics, intimate partner violence and sexual exploitation, healthy relationships, social and structural determinants, personal responsibility, risks for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancy, access to sexual and reproductive health care, and the benefits and disadvantages of condoms and other contraceptive methods.” ( Santelli et al., 2017).

Employing a multifaceted approach that seamlessly integrates a meticulous survey, insightful listening sessions, and targeted focus groups, the study unveils a nuanced understanding of the intricate, intersectional factors shaping sexual health disparities within this demographic.

The incorporation of a reproductive justice lens accentuates the interconnectedness of race, gender, and socioeconomic elements in influencing sexual health outcomes.

Rooted in cultural relevance, the research ardently advocates for tailored interventions, epitomized by the “Get Smart B4U Get Sexy” curriculum, adept at addressing the unique cultural norms and values embedded within the Black community.

The study suggests that a strategic blend of traditional school-based programs with online resources may yield the most favorable outcomes in terms of participant satisfaction.

Further research should explore the specific components of community-based programs that contribute to their comparatively higher ratings and inform the development of comprehensive and effective sexual health education initiatives.

The qualitative richness derived from listening sessions and focus groups surpasses the confines of quantitative data, providing firsthand narratives that humanize the challenges faced by Black youth.

Recommendations for culturally competent health education programs, collaborative efforts with schools, utilization of online resources, and the establishment of youth advisory boards present actionable insights for policymakers and practitioners, bridging the often-discernible gap between research findings and practical, impactful interventions.

In recognizing the intersectionality of race, gender, and socioeconomic factors in sexual health education, this research underscores the pressing need for interventions that holistically address the diverse needs and preferences within the Black youth demographic.

Applying a reproductive justice lens not only emphasizes the importance of content and quality in health education and services but also underscores the critical understanding of the social dynamics, communication preferences, and support structures that mold the sexual health experiences of Black youth.

Insights derived from listening sessions and focus groups underscore the urgency of culturally attuned interventions, shedding light on the pivotal role initiatives like the “Get Smart B4U Get Sexy” curriculum play in mitigating sexual health disparities.

In essence, the presented narratives and recommendations coalesce into a potent force for empowering Black youth, disassembling entrenched barriers, and nurturing an educational environment conducive to well-informed sexual health decision-making.

The findings echo the imperative for inclusive, informative curricula, culturally sensitive approaches, and precisely targeted interventions to confront pervasive healthcare disparities, ensuring equitable access to healthcare services for Black youth.

This synthesis of quantitative and qualitative data not only provides a holistic understanding of the sexual health landscape but also illuminates avenues for future research and policy development.

In summary, this research paper not only addresses critical gaps in the literature but also emerges as a compass for actionable recommendations, poised to foster positive sexual health outcomes within the diverse and vibrant Black youth demographic.

This research advocates for a collaborative effort among educators, policymakers, and program administrators to enhance the comprehensiveness and impact of sex education.

This involves continuous evaluation, identifying specific areas for improvement, and fostering an environment that promotes informed decision-making and empowerment in matters of sexual health.

The synthesis of quantitative data and qualitative considerations provides a robust foundation for future research and policy development in the realm of sexual education.

References

Boutrin, M. C., & Williams, D. R. (2021). What Racism Has to Do with It: Understanding and

Reducing Sexually Transmitted Diseases in Youth of Color. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland), 9(6), 673. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare9060673

California Department of Education. (2023, November 15). California’s Health Education Initiatives.

California’s Health Education Initiatives – Health Education Framework (CA Dept of Education). https://www.cde.ca.gov/ci/he/cf/cahealthfaq.asp#:~:text=State%20law%20defines%20comprehensive%20sexual,EC%20§%2051931%5Bb%5D).

California Department of Social Services. (2023, October). Performance and Outcome Data on the

Implementation of Sexual and Reproductive Health Training and Education. Children and Family Services Reports. https://www.cdss.ca.gov/inforesources/information-resources/program-and-legislative-reports/children-and-family-services-reports

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diagnoses of HIV infection in the United States and

dependent areas, 2019 HIV Surveillance Report 2021. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

Division of HIV and STD Programs (DHSP) . (2022, July 27). Sexually transmitted infections Los

Angeles County, 2021. Sexually Transmitted Infections Los Angeles County, 2021.

http://publichealth.lacounty.gov/dhsp/Reports/STD/2021_STD_Snapshot_LAC_Only_04.03.23_

Final.pdf

Dorsey, M. S., King , D., Howard-Howell, T., & Dyson , Y. (2022, March 21). Culturally responsive sexual health interventions for black adolescent females in the United States: A systematic review of the literature, 2010–2020. Children and Youth Services Review. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0190740922001165

Mon Kyaw Soe, N., Bird, Y., Schwandt, M., & Moraros, J. (2018, December 11). STI Health Disparities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of preventive interventions in educational settings. International journal of environmental research and public health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6313766/

Salam, R. A., Faqqah, A., Sajjad, N., Lassi, Z., Das, J. K., Kaufman, M., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2016, September 21). Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health: A systematic review of potential interventions. Journal of Adolescent Health. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1054139X16301689

Santelli, J. S., Grilo, S. A., Lindberg, L. D., Speizer, I. S., Schalet, A., Heitel, J., Kantor, L. M., McGovern, T., Ott, M. A., Lyon, M. E., Rogers, J., Heck, C. J., & Mason-Jones, A. J. (2017, June). Abstinence-only-until-marriage policies and programs: An updated … Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage Policies and Programs: An Updated Position Paper of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(17)30297-5/fulltext

U.S. Department of Health and Human Service. (2021). Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) – health, United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/hus/topics/HIV.htm

Vanwesenbeeck, I. (2020, May 29). Comprehensive Sexuality Education. DSpace Home. https://dspace.library.uu.nl/handle/1874/414795

Zellner Lawrence, T., Henry Akintobi, T., Miller, A., Archie-Booker, E., Johnson, T., & Evans, D. (2016, December 24). Assessment of a culturally-tailored sexual health education program for African American Youth. International journal of environmental research and public health. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5295265/